“Book of Hours,” 15th century. Tempera, ink, and gold leaf on parchment. Maker(s) not known by WCMA. Kingdom of France (present-day France).

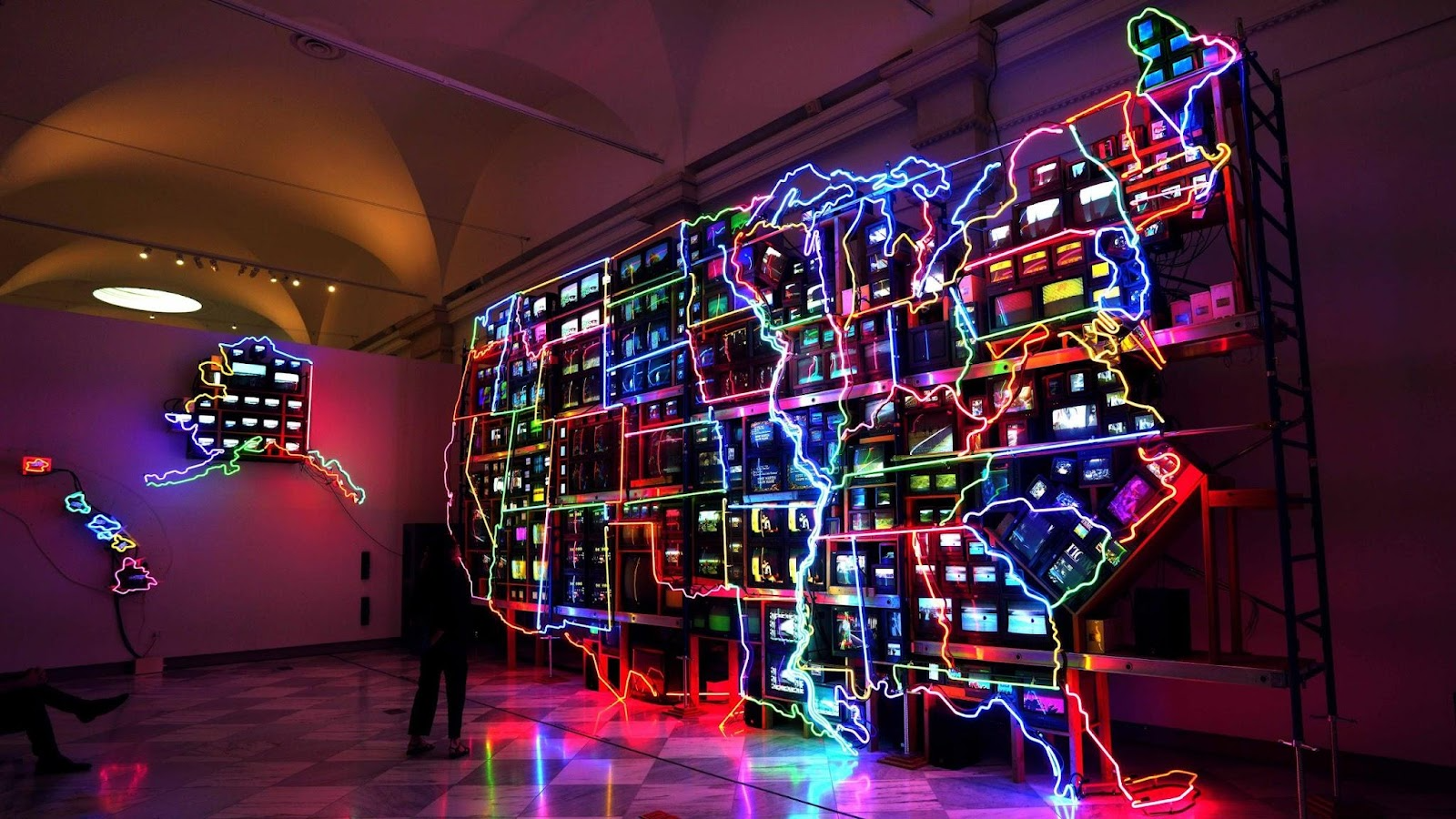

WILLIAMSTOWN — In a small second-floor gallery at Williams College Museum of Art the walls are painted red — Moroccan red, to be precise. Rustic terra cotta tiles cover the floor, dark oak beams stripe the ceiling. Hidden for a decade, the gallery’s diamond paned windows with stained glass insets, uncovered five years ago, now let daylight enter.

Reclaimed in 2017, but only recently freed of its muted, neutral walls, the medieval gallery is home to a new, ongoing exhibit, “Embodied Words: Reading in Medieval Christian Visual Culture,” of more than two dozen works from the 12th through 16th centuries taken from WCMA’s collection and manuscripts from Chapin Library.

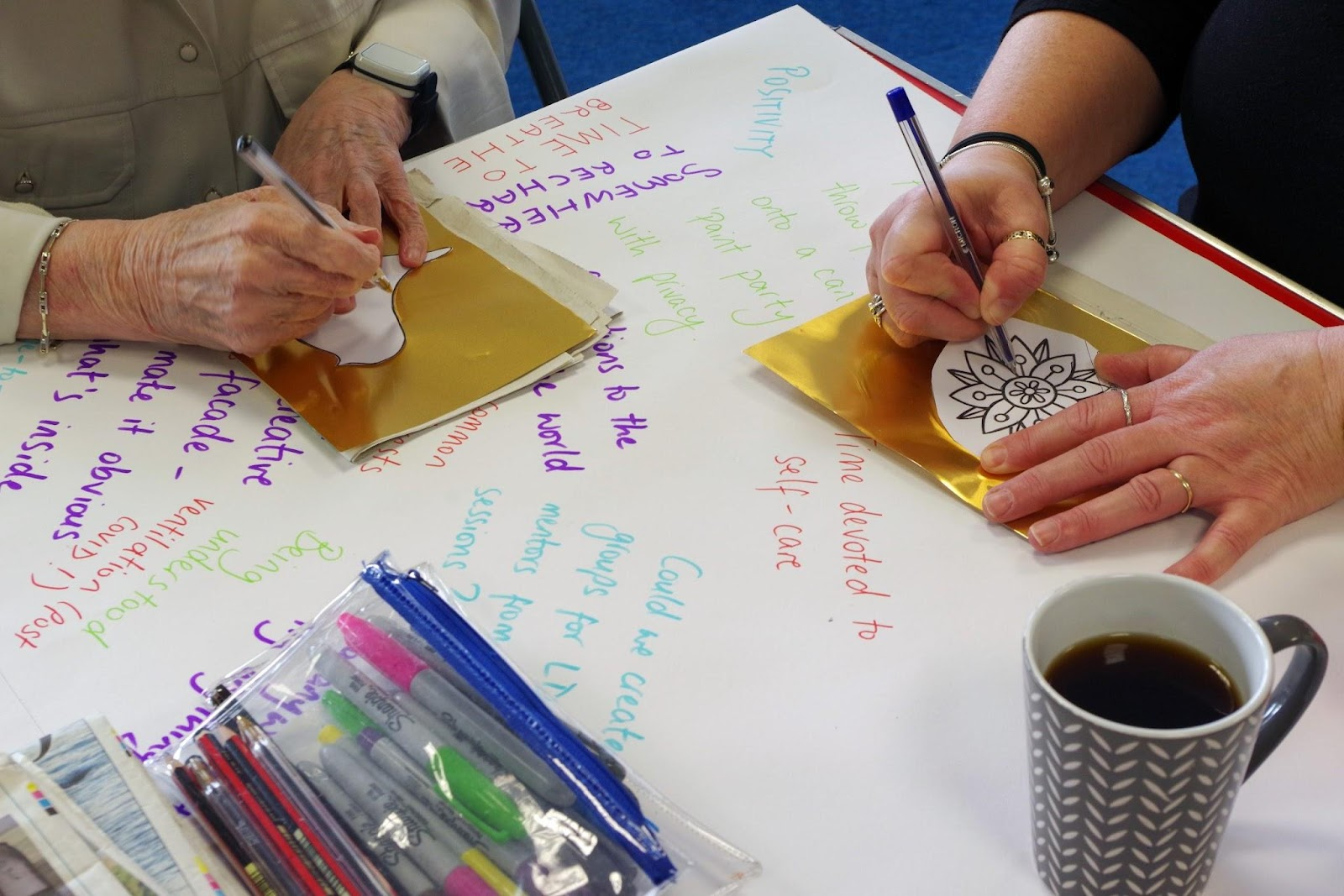

“In the Middle Ages, reading was thought to transform you, physically and spiritually. Medieval people believed that words written and read, spoken and heard, could imprint on the brain, heart, and soul,” writes WCMA Curatorial Assistant Elizabeth Sandoval, in the opening of the exhibit, which she curated with assistance from Nicholas Liou, Mellon Curatorial Fellow, and Claire L’Heureux.

Sandoval, a medievalist whose Ph.D thesis explored 15th-century books, text and imagery, worked closely with Chapin Library Special Collections Librarian Anne Peale to select art works, artifacts and bound manuscripts from the museum and library’s extensive holdings.

“Dormition of the Virgin,” ca. 1475–1485. Limewood. Maker(s) not known by WCMA. Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany).

“Words are all around us,” Sandoval said by phone after a rainy day in Florence, Italy, where she was leading an art history student tour.

“We see words in books, paintings, sculptures and in pieces of architecture,” she added, in both homes and public spaces.

The exhibit and her doctorate field of study “seemed to fit together very nicely,” she said. “Maybe I was biased when I was looking at these objects, in that they represent what I had written about.

“It’s a small gallery, the artworks have space but are also in dialogue with each other.”

An art historian with a bachelor’s degree in English literature, Sandoval has always loved reading.

“Ever since I was a little girl. I remember liking books that looked like manuscripts because they had pictures,” she said.

In medieval times, however, not everyone could read and write, she said.

“Reading was gendered, and by class.”

In one illustration, she points out, “Both [the Virgin] Mary and [St. Luke] are sitting at desks, but only [St. Luke] has a writing utensil. Women would teach their children Latin and how to read. Theologians could read and write.”

Exploring WCMA’s 15,000-object collection in person surprised her with its breadth and content. Along with many familiar works, Sandoval unearthed some rarely if ever seen pieces.

One fragment from a church in France “is a beautifully curved piece of stone in high relief,” she said. “A headless prophet or king [is] holding a book in front of his chest, right over his heart. It’s only a torso, [but] it has a presence.”

In a late 15th-century Spanish painting, white-bearded Saint Anthony Abbot holds up a book of prayer, his eyes engaging the onlooker intently. “He’s asking the viewer to pray,” Sandoval noted. With a gilded halo and foliate framing his head, symbols of his sainthood surround him: a staff and bell in his hands, a wild boar and flames at his hem.

The painting’s pristine condition reflects three years of painstaking restoration (after a hanging wire failed) by Williamstown Art Conservation Center’s Sandra Webber.

Anchoring the gallery is a massive 12th-century limestone baptismal font, a longtime fixture due to size and weight. With four sculpted heads each facing a different direction, it provides a temporal context that brings the medieval art into focus.

“St. Anthony Abbot,” ca. 1460–1470. Tempera on panel. Attributed to Pedro García de Benabarre, (active 1455–1480). House of Catalonia, Crown of Aragon and later Crowns of Aragon and Castilla (present-day Kingdom of Spain).

MEDIEVAL MANUSCRIPTS ON VIEW

The exhibit includes several ancient texts, six on loan from Chapin Library — manuscripts and a book mostly from the 15th-century. Also on view is a seventh text — a manuscript from WCMA’s collection that outside of this showing is on long-term loan to Chapin Library.

“One is [a] majestic antiphonary used by monks or priests to sing during Mass,” Sandoval said. “It’s huge so that several people could read it at once and from a distance.”

“There’s [also] a very sweet tiny psalter made by a nun,” she added. “Writing is creating a book, and also a devotional act.”

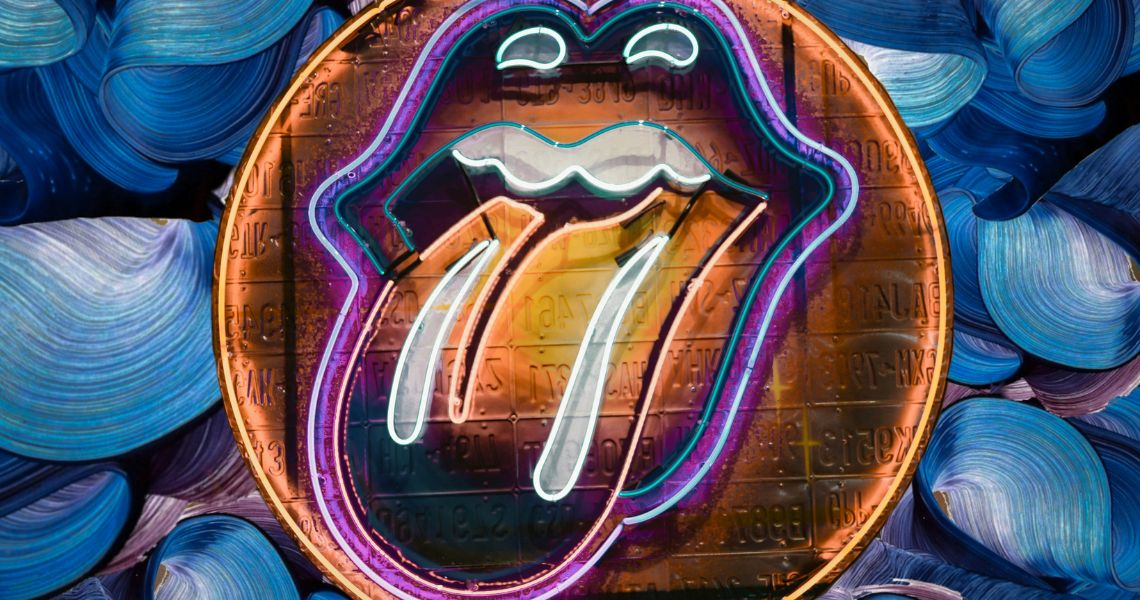

Also on display are four “Books of Hours” and a 13th- to 14th-century miscellany, its separated binding showing early use of stitching.

With Sandoval overseas, senior curator of American and European art Kevin Murphy toured the exhibit accompanied by Peale.

Inspired by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s Tapestry Room, Murphy said the original purpose of WCMA’s gallery was to house its medieval collection. After being boxed in by neutral gallery walls for a decade, “We brought it back a few years ago, and uncovered the walls and windows.”

The current exhibit shows “how [people] were using books at the time, and also how they were emblematic of other things,” Murphy said.

Sandoval really combed the collection, he said, unearthing many rarely seen objects.

RARELY SEEN OBJECTS

A limewood relief carving, “Dormition of the Virgin,” depicts the passing of the Virgin Mary, with iconographic elements including prayer books, candle, holy water, and incense. Identifying what appeared to be an added candle holder stem, “You can imagine how a single candle flickering would have animated all of the crevices and made it look very much alive,” Murphy said.

Two 16th-century panels show pious, well-heeled donors with Saints Barbara and John, offering a time-traveling view of artistic and religious patronage. St. Barbara’s attributes of a book and castle are also visible in a nearby wooden sculpture of the saint, Murphy noted.

A three-panel painting, “The Passion of Christ,” relating the entire story is “almost cinematic,” Murphy said. Copied from a work by Flemish painter Hans Memling, the complex, densely populated scenes evoke later paintings by Bruegel.

“Medieval people developed sophisticated abilities to read paintings,” writes Sandoval the exhibit’s wall text. “This Passion triptych encourages a journey alongside Christ on the serpentine path to his Crucifixion and Resurrection.”

There are about 40 pre-modern European codex (bound) manuscripts in the Chapin collection, primarily used in teaching Williams students.

“It’s really exciting to see them in this much more public space,” Peale said.

All the exhibit’s manuscripts use animal skin parchment, she said, its durability the reason why such intricate, laboriously fabricated tomes still exist today.

HANDWRITTEN TEXTS

The writing is surprisingly tiny.

“Parchment is expensive,” Peale noted, “so to save space it was common to have a very small, compact hand.”

Fortunately for scribes, she said, scriptoria “were some of the best-lit areas in a monastic environment.”

Elaborate polychromatic illustrations and embellishments added rich visual content to the mostly handwritten devotional books (one is printed). Even the tiny 9-by-6-centimeter psalter has seven full-page and 211 smaller miniatures on its 223 leaves.

“The quantity of illuminations is really enormous,” Peale said.

“Books of Hours,” Peale said, are prayer books for lay people — very personal, often highly decorated objects The printed example demonstrates considerable technical achievement, she said, as parchment’s smooth surface causes printer’s ink to smear.

MOROCCAN RED

Sandoval noted the importance of the gallery’s newly painted red walls, how they connect to the practice of manuscript rubrication, coloring initials red to identify key passages, phrases and section headings. It also picks up on the reds in the artworks, and relates to blood through the theme of embodiment.

“This the first time since I’ve been here that we’ve done this really robust collaboration with Chapin,” Murphy said. “It’s a way to bring people together into one space and have the two collections intermingle.”

“Reflect on how medieval reading practices shape how, what, and where you read today, even in digital formats.” Sandoval wrote. “Whether we are turning the pages of a codex or scrolling down a screen, reading is always an embodied act.”