I love good poetry. I can spend hours at a time reading excellent poetry, particularly reading it aloud to taste its musicality and experience the words in three dimensions. Few among us are capable of writing good poetry, though. I know because I’ve also seen my share of bad poetry. As an editor, I occasionally am called upon to edit a series of poems. I approach such an opportunity cautiously, for I have come across few contemporary writers who can actually write good poetry.

Well, maybe I should modify that last sentence: I have found few contemporary writers (except for those already published and/or famous) who have written good poetry. Maybe they could write good poetry if they had a better understanding of how to go about it. Anyone who can communicate through poetry has achieved the ultimate writing craft, so creating a fine poem is a worthy goal.

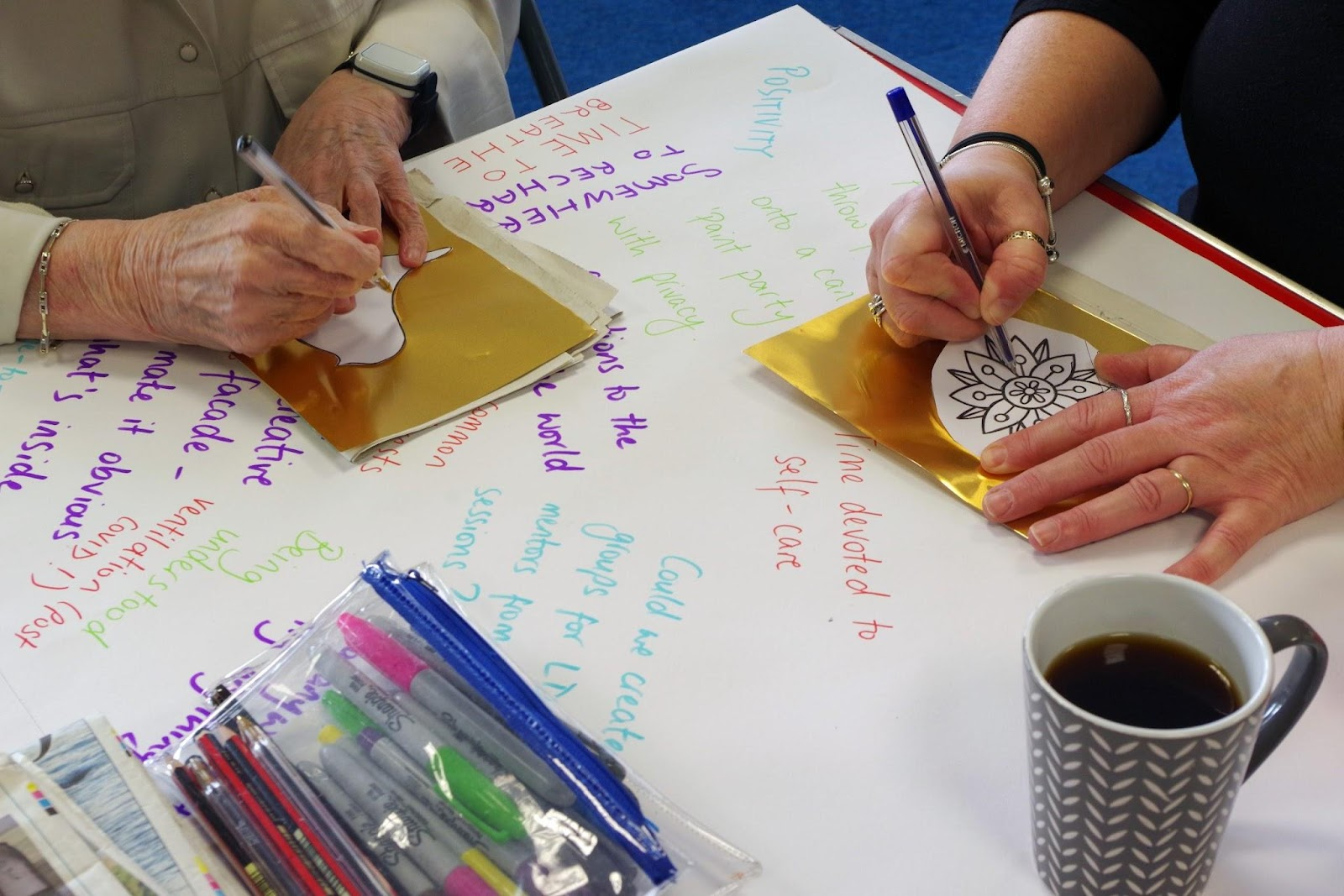

I’m not a poet. I am a connoisseur of fine poetry. I can help readers fully enjoy a good poem, and I can help aspiring poets dramatically improve their craft, but I don’t claim to be a poet myself. Still, I’ve had enough success with inexperienced poets that I think I have some insight to offer, and that’s the point of this article. If you feel, deep inside, that you could write a really fine poem, you probably can. If you sense an inner need to write effective poetry, then you probably should try. If you have not yet mastered that art, perhaps you simply need some guidance.

Verse is not Necessarily Poetry

Let me first distinguish between poetry and verse, because I believe that is where most people go wrong. Verse, you see, is the musical arrangement of words for a melodious or metrical effect. We all like to play with rhyme and economy of words and imagery. If you take a well-known tune and write new lyrics to celebrate your best friend’s birthday, you’ve written verse, not a poem. If you hit upon a rhythm and a clever theme and then arrange funny or mushy phrases around that rhythm and theme so that they rhyme (or nearly do), you’ve written verse, not poetry. What you read in greeting cards, 99.9% of the time, is verse, not poetry.

That, of course, begs the question: What is poetry? In my opinion, poetry often (but not always) includes all the characteristics of verse, but it has so much more, insight and emotion being the two most critical factors. So, can you take a little piece of verse, inject a bit of insight and a dash of emotion, and end up with a poem? I don’t think so. Maybe that’s why the world is immersed in verse but poetry-poor. Many of us can write verse; I have done it often. Few successfully write a poem, however. The reason for that phenomenon, I believe, is the sacred and mysterious process of birthing a really good poem. While verse can spawn from a scrap of music or a second-rate jingle, poetry is born of things precious and rare.

Insight Born of Experience

A true poem begins with an experience. We all have a thousand experiences a day so, I suppose, each of us comes across the raw material of a thousand poems everyday. Why don’t those poems materialize? Why do a handful of such experiences evolve, a little later, as cute or clever verse, but most just disappear? What transforms an experience into a poem? Consider what the icons of poetry have done with a jar of cold plums, a red wheelbarrow, a stone fence, grass. Truly, it is not the experience itself that ignites the poem. I see stone fences everyday, yet I’ve never written anything to rival “Mending Wall.” Most wheelbarrows I come across are not red, but, even if they were, would I realize how much depends on a wheelbarrow? Have you or I ever seen Chicago as Carl Sandburg saw it, “husky… brawling… city of the big shoulders,” or a snake as Emily Dickinson saw it, “a narrow fellow in the grass”? I’ve heard a fly buzz – I’ve heard many flies buzz – yet I’ve never associated the sound with my own death. Hmmm…

What transforms an experience into the stuff of poetry, I am quite certain, is the insight the experience brings. And here I use that word very literally: to see into the experience. Thousands of people ride ferries everyday, but Edna St. Vincent Millay saw the ferry-riding experience as a metaphor for her crowd’s Roaring Twenties lifestyle: “We were very young, we were very merry/ We rode back and forth all night on the ferry.” And so her experience, offering insight, became the stuff of poetry. Thousands of us, at various points in our lives, look at spiders weaving their webs, but it was Walt Whitman who took insight from “a noiseless, patient spider” as he did from a starry night sky viewed right after a boring lecture on astronomy. A poem begins, very often, with the insight gained from experience, but it is insight so crystal clear that you know it to the depths of your heart and the soles of your feet. Often that insight comes as suddenly as a punch to the jaw; it can even take your breath away.

A Psychic or Emotional Response

Most all mature adults have gained insight from their experiences, yet few of us write poems about those insightful experiences. So what comes next? We generally learn from experience, grow from the insight therewith provided, and evolve as persons, but do we write poetry about it? No, and I’ll bet many of us could! For reasons I will not try to identify, the vast majority of us fail to respond to insightful experiences as poets respond: A poet is immersed in the insight, filled up with the experience, bowled over by the new understanding, consumed by the emotion, inspired by the possibilities. So that, I believe, is the next step: an emotional or psychic response to an insightful experience. Writers of verse probably skip that step.

The highly charged response of the poet does not have to be a lesson learned. It might be the awakening of a new, hitherto unfelt emotion, or a deeper level of pleasure from the same old experience, or a sense of wonder or humor or understanding. The point is that poets stop to fill themselves with the feelings and thoughts – fill themselves up until something has to give. And that takes us to the fourth step in the birth of a poem: the need to express the new insight, emotion, understanding or desire. Only when we are filled up do we have the urgent need to express.

Still, we haven’t yet reached the crux of the poetry issue. Many people are moved by an experience, do take the time to feel the emotions and insights, and do produce some sort of communication directed at the rest of humanity. What is produced is often prose: a letter to the editor (or, on a more personal basis, a letter to a relative or old friend); a screaming, raging email message; a carefully composed essay; a glowing testimonial. All prose. Others now make a stab at poetry, and they produce things made out of words, arranged in stanzas, desperate to communicate, not quite there. All prosaic. What does the successful poet do differently?

Connecting Insight to Image

The poet makes a connection that others fail to make, and that connection gives genesis to the seed of the new poem. In his or her need to communicate this overwhelming experience, the poet seeks and finds an image to which this new insight can be compared – something of the everyday world, an object or event or process the reader will recognize as familiar, understand, and readily grasp. Now we have the birth of figurative language, the metaphor or simile or personification that lies at the heart of the new message. In a sense, this comparison, never before made, is the message. This is the new connection, a deeper level of insight, a creative way of seeing; without this, a would-be poem is merely words. So, when we read that “the fog comes in on little cat feet” we share a unique connection made by a poet who saw fog in a whole new way. Now the poet (in this case Carl Sandburg) has found the vehicle of expression: a unique, creative comparison that instantly brings his experience to our doorstep. We all know something of little cat feet. Sandburg’s connection between the fog and the little cat feet is an act of creative genius.

Musicality Enhances Insight and Image

That creative accomplishment, however, is not yet the making of a poem. Now the other elements of poetry come into play. Economy of words is, of course, the hallmark of poetry, the feature that most differentiates it from prose. And when words are used economically, there is not a word, not a letter, not a sound to spare. Every carefully selected word has a sterling ability to convey the sound and sense of a particular facet of the idea. Next come the musical qualities: rhyme, rhythm and meter, repetition, alliteration. Now, all of these forces can be developed simultaneously, but this is the important thing to keep in mind: the insight comes first, then the image or vehicle, and only then the words and music. Those verbal tools must elucidate the insight and support the image.

Words and music without insight and image produce only verse (or drivel, sometimes). The same is true for cute similes and metaphors embedded into the text for no other reason than poetry’s traditional use of similes and metaphors. Figurative language that is not part and parcel of the message – born of the insight or inherent in the fundamental image – is only window dressing, sure to fade as the seasons change. The same can be said of forced rhyme, lines manipulated all out of proportion to make the ending sounds alike: mere decoration, but not the stuff of poetry. Using onomatopoeia because you can, or personifying an inanimate object because you can – these are techniques of verse, not of poetry. All the verbal and musical components of a good poem serve the central insight and interlock naturally with the central image. That is poetry.

It would now only make sense, I believe, to present to you a poem that I think is outstanding in every one of these ways, and so I shall. I choose “Gold Glade” by Robert Penn Warren, not a popular poem (although a famous author), but one that stirs my heart and my intellect with every reading, so near to the perfect poem it is. I should warn you: it takes several focused readings to gather it all in.

Gold Glade

Wandering, in autumn, the woods of boyhood,

Where cedar, black, thick, rode the ridge,

Heart aimless as rifle, boy-blankness of mood,

I came where ridge broke, and the great ledge,

Limestone, set the toe high as treetop by dark edge

Of a gorge, and water hid, grudging and grumbling,

And I saw, in mind’s eye, foam white on

Wet stone, stone wet-black, white water tumbling,

And so went down, and with some fright on

Slick boulders, crossed over. The gorge-depth drew night on,

But high over high rock and leaf-lacing, sky

Showed yet bright, and declivity wooed

My foot by the quietening stream, and so I

Went on, in quiet, through the beech wood:

There, in gold light, where the glade gave, it stood.

The glade was geometric, circular, gold,

No brush or weed breaking that bright gold of leaf-fall.

In the center it stood, absolute and bold

Beyond any heart-hurt, or eye’s grief-fall.

Gold-massy in air, it stood in gold light-fall,

No breathing of air, no leaf now gold-falling,

No tooth-stitch of squirrel, or any far fox bark,

No woodpecker coding, or late jay calling.

Silence: gray-shagged, the great shagbark

Gave forth gold light. There could be no dark.

But of course dark came, and I can’t recall

What county it was, for the life of me.

Montgomery, Todd, Christian-I know them all.

Was it even Kentucky or Tennessee?

Perhaps just an image that keeps haunting me.

No, no! in no mansion under earth,

Nor imagination’s domain of bright air,

But solid in soil that gave it its birth,

It stands, wherever it is, but somewhere.

I shall set my foot, and go there.

Robert Penn Warren

A Life-changing Experience, not Mere Technique

I had read this beauty at least six times before I ever realized the absolutely perfect rhyme scheme: ababb. Attention is so focused on the discovery of the achingly beautiful tree that the rhyme is barely noticeable. The simile so perfectly complements the feeling and actions of the speaker that it hardly calls attention to itself: “heart aimless as rifle.” The “grudging and grumbling” water is so naturally personified that it does not shout “personification!” The same can be said of this subtle personification: “where cedar, black, thick, rode the ridge.” The metaphors are both brilliant and inherent: “leaf-lacing… bright gold of leaf-fall… heart-hurt… eye’s grief-fall.”

“Gold Glade” is a wonder of musicality, yet those techniques always serve the insight and image. The alliteration (“rode the ridge… boy-blankness… ledge/Limestone… foam white on/Wet stone, stone wet-black, white water tumbling… glade gave) and assonance (“woods of boyhood… grudging and grumbling… mind’s eye… glade gave… far fox bark… late jay”) serve to communicate the wonder of the unparalleled tree-beauty, not to call attention to their own cleverness or to intellectualize a barren line.

Reading this poem is to vicariously experience the speaker’s boyhood discovery of a tree so powerfully lovely that it has haunted him and drawn him back throughout his lifetime. As precisely and musically worded as Robert Penn Warren’s poem is, it is absolutely the recounting of a life-changing experience rather than a display of words or poetic techniques. There can be no doubt this poem was born of the discovery of a serene glade, filled with the golden rays of the setting sun, dominated by an oak tree of breathtaking magnificence. From that experience developed the birth of a superior poem.