The representation of Sunderland AFC, its fans and its games in the arts is a topic we revisit periodically here on Roker Report. There’s clearly a reason why we are drawn back to reflecting on graphic representations of the beautiful game, and it’s something that I’ve been thinking about a lot over the last few weeks.

I’ve spent much of that time laid up with covid-19 and looking at the Chris Cummings print of a boy and his dad starring out across at Roker Park that I was bought a couple of years ago, which hangs on my bedroom wall.

Just why do I love it so much? Why is going to see Frank Styles’ new mural of ex-Sunderland Lioness Demi Stokes in South Shields on my “must do” list when I’m next back up in the north east? And why did I get excited when I saw Kathryn Robertson’s illustrations that accompanied the club’s season ticket renewal campaign when it came out the other week?

What is it about the art and design of Sunderland AFC that makes it such an important part of our football culture?

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23356460/IMG_DAFE78B6D63C_1.jpeg)

To begin with, I must acknowledge the long history of the genre, but I won’t dwell too much on the grand depiction of Sunderland’s clash with Aston Villa at the old Newcastle Road ground in 1885 by Thomas Hemy that hangs proudly in the main entrance of the Stadium of Light here.

Its current position at the centre of the exclusive shining marble and polished metal foyer sets it apart from the masses – a close-up view is generally reserved for stadium tour parties, executive box dwellers, and club officials. The match-going public is left with a partial glimpse, the view obscured by security guards and the reflection of many square metres of plate glass.

It may be a work that is instantly recognisable and an important part of our history, but it is not public or accessible to your everyday punter. It might be about us, but isn’t really for us, it’s more for them.

Instead, I want to look at some of the ways that artists have brought the game on Wearside and depictions of the people who make it – the players and the fans – into our everyday lives.

And through talking to three very different contemporary artists that I admire – Cummings, Styles, and Robertson – I’ll try to answer those questions that spun around my feverish mind and learn a little more about the mercurial connection between the visual arts and football culture on Wearside.

But first, some history.

Papers, mags and baccy

For decades, the main way that football and art intersected via the produce procured by ordinary people from the tobacconists and newsagents on the way to and from work.

Indeed, in the earliest days of the game, it was sketches of footballers in action that accompanied reports in the newspapers that first brought images of the newly standarised association rules matches to huge audiences in the booming conurbations of Victorian Britain.

Often depicted alongside other dramatic arts and theatrical entertainments, it’s clear that at this time football was still considered somewhat of a gentile pursuit where the amateur, aristocratic “Corinthian Spirit” was still valued highly.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23353948/Screenshot_2022_03_29_at_22.59.39.png)

These back and white line drawings have the air of self-improvement, discipline and values of “muscular Christianity” that proponents of football and other organised sports sought to imbue on the proletariat from above.

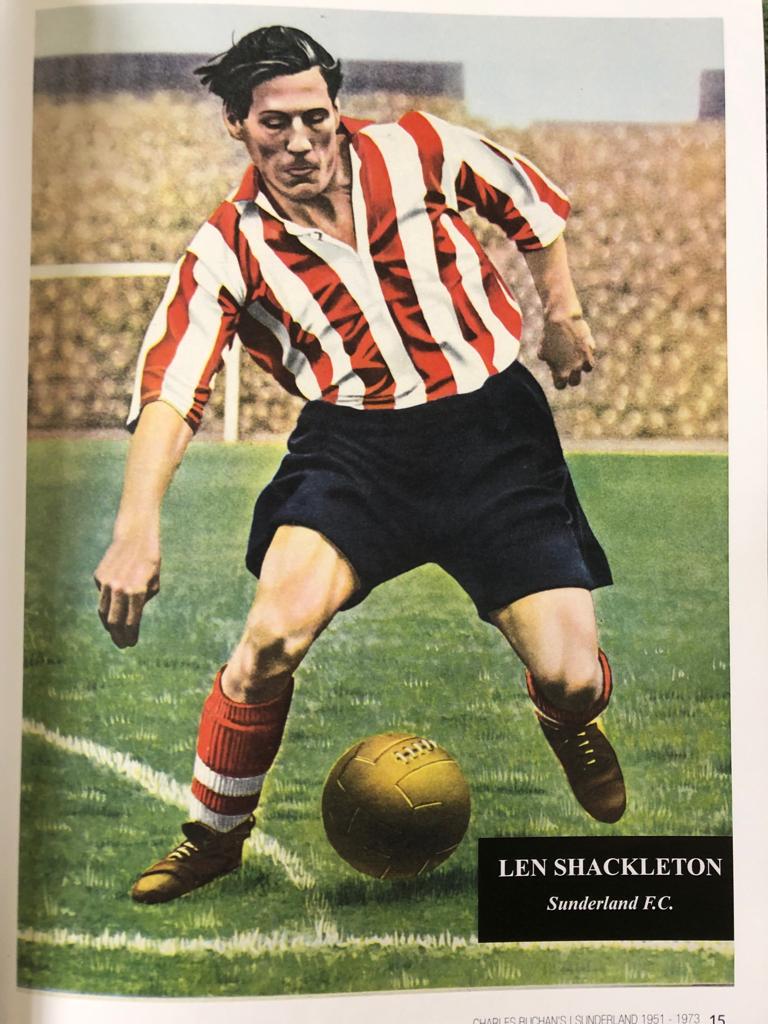

A more colourful yet deadly medium for football illustration after the turn of the 20th century was the cigarette card. Hand-drawn series produced by the likes of Churchman’s, Ogden’s and Gallaher’s from the pre-Great War era reproduced football action in colour as working people had never seen before, and made celebrities of those like Sunderland skipper Charlie Thomson in the process.

A fine example is the 1914 Churchman card, which also depicted the scene on matchday at Roker Park with the grand old ground’s stands clearly visible in the background. As with the line drawings in the newspapers, the carefully coloured illustrations were later replaced by photographic cards, which in fag packets were often colourised for greater emphasis.

The tradition of illustration, however, lived on after the Second World War in boys’ magazines and football annuals – as well as in the fantasy world comics like Tiger, and then Roy of the Rovers.

Sunderland’s legendary forward Charlie Buchan, once he retired from the game, created a magazine that chronicled the British game and regularly featured graphics of Sunderland AFC – giants of the mid-century English game – in action.

These iconic images were reminiscent of those cigarette card miniatures, and they too were replaced by photographs in later editions.

But together, the cigarette cards and magazine pin-up posters set the tone for how, in the time before the ubiquity of colour photography and colour film, real-life football was portrayed from then on.

They became the standards – a visual language of the game the echos of which are still detectable even in the computer-generated graphics that accompany matchday TV coverage today. They also form the hinterland of much of contemporary football art, a topic which I will explore in the rest of this short series.

The mists of time

For many of us, however, our fellow supporters are as – if not more – important to our experience following the club as the players on the pitch. The same familiar faces, the local characters, the fella who you hugged at Wembley when it looked like we’d finally won and sobbed on your shoulder when our dreams were dashed once again, but most of all the friends and family we share the matchday experience with.

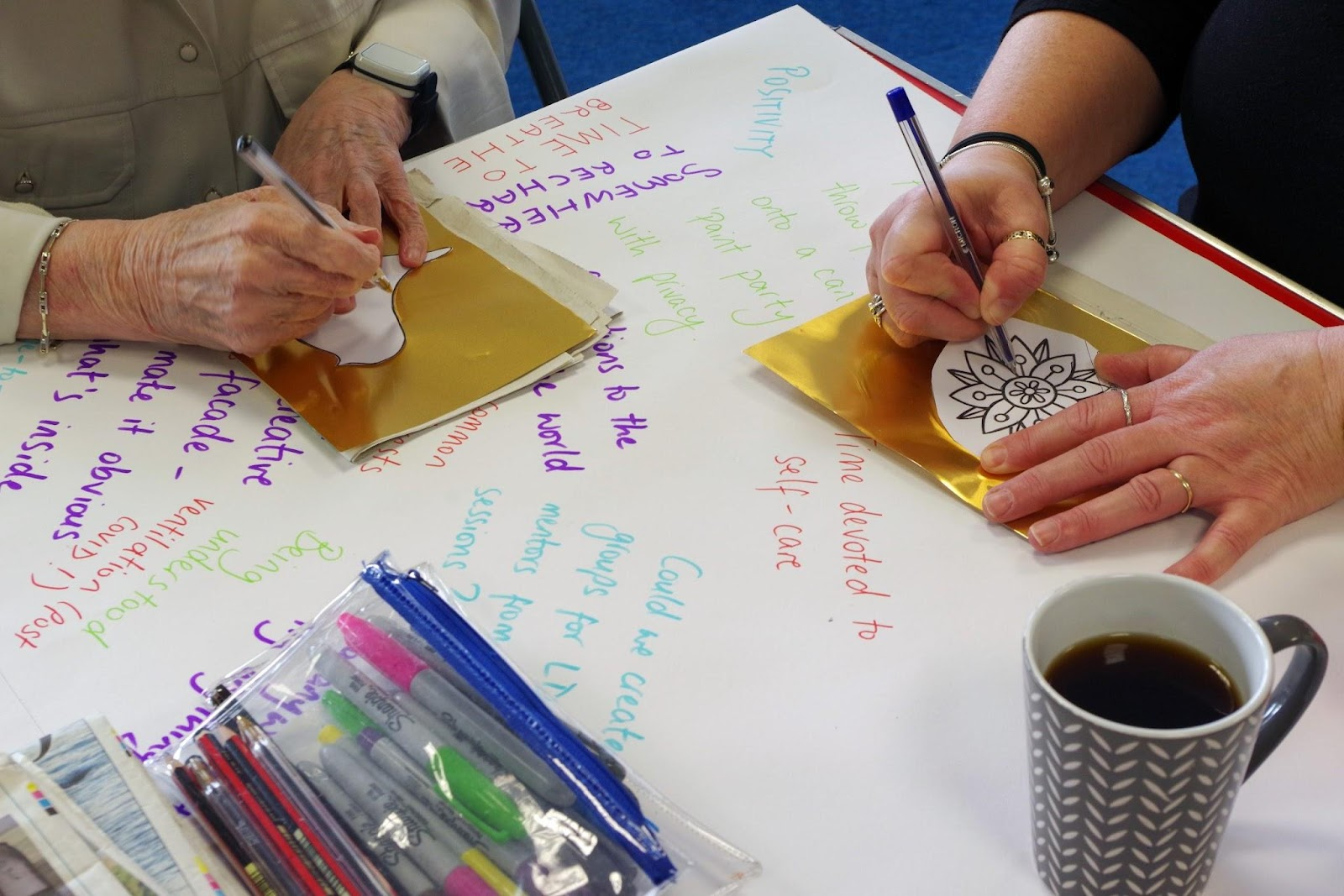

It’s the family that forms the centre of Chris Cummings paintings. Chris kindly answered a few questions I sent him over recently and told me that his inspirations include the County Durham pitman painter Norman Cornish and the contemporary Scottish impressionist Alexander Millar, whose styles and subject matter – the everyday lives of working-class people – he brings to his depictions of football crowds.

He’s unambiguous about the emotions that sit behind his work and make it so popular with his fellow Sunderland supporters:

My work and subjects are nostalgic and my aim is to create a style that is instantly recognisable through the characters with the oversized bobble hats and big scarves. I want my paintings and sculptures to evoke memories that people have had especially from Matchdays.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23353803/855031910.jpg)

As traditional as his works may be, his method of getting his work out to the masses is very modern. Chris realises that social media has played a huge part in embedding his paintings in the consciousness of the fanbase – the biggest philistines amongst us recognise it instantly because it’s ubiquitous online.

Cummings tells me, “Supporters are the main focal point for most of my work because it’s something I can relate to and recreate from my experiences.”

Chris and I are about the same age, and our shared memories of Roker Park and the early days of the Stadium of Light loom large in his repertoire.

Being taken to the match with our parents is a common childhood experience for so many boys and girls in our city, it’s a vital and essential part of our upbringing and something that, as parents, we seek to emulate with our own offspring. That’s the power of Cumming’s art, and why it probably sells pretty well in the lead up to Father’s Day each year.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23353751/3DBDC53E_8360_40D2_86B1_CC380B8FBCAC.png)

Image courtesy of Chris Cummings

That tendency to hark back to a lost, golden childhood era – simpler, mythical, halcyon days some might say – that is lost in the mists of time, is something that an artist Chris admires, Paine Proffitt, has also sought to explore to great effect and to widespread acclaim.

Although an ex-pat American not a Wearsider, Proffitt’s retro, cartoonish twist on socialist modernism has been featured on the covers of books about our club and Sunderland is a perennial subject matter for this sports-mad, Anglophile Picasso fan.

His work has a slightly harder, masculine edge to it than Cummings’, one that is reminiscent of both Spanish civil war propaganda posters, celebrating mid-20th-century footballers as working-class warriors, as well as recalling aspects of the cigarette card art of over a century ago. We’ve seen Proffitt’s iconic images on the cover of Sunderland matchday programmes, promoting Netflix documentaries, and on books about our club’s history.

Whether it’s footballers themselves or the crowds who watch them, people want to consume this art – they will pay for it, they will hang it on the walls in their homes, collect it in folders, and display it on their coffee tables. If it’s particularly rare, they will bid silly amounts for it in online auctions.

Finished season 2 of Sunderland Til I Die … if you ever wanted to see David Brent run a football club then boy are you in luck. pic.twitter.com/44HwzhVdL9

— Disgraced Cosmonaut (@Paine_Proffitt) April 3, 2020

So far I have looked at images that are held privately – objects that we personally treasure and will no doubt pass down to our Sunderland-supporting descendants. In the second part, I will look at the works which adorn our public spaces and both celebrate the glorious past while pointing toward a future that, despite the travails of the past half-decade or more, still holds much promise for our club and our city.

I also will speak to some of the artists who are currently making waves, and creating a new pop culture at the intersection of art, football and indeed music in our beautiful city by the sea.