Heritage-mapping attracts the large and slender, the acknowledged and unknown previous to the existing. All through my residency at the Aminah Robinson dwelling, I examined the impulses powering my prose poem “Blood on a Blackberry” and located a kinship with the textile artist and writer who built her household a creative risk-free area. I crafted narratives by means of a blended media software of vintage buttons, antique laces and fabrics, and textual content on cloth-like paper. The beginning stage for “Blood on a Blackberry” and the crafting for the duration of this job was a photograph taken far more than a century in the past that I found in a family album. Three generations of ancestral moms held their bodies nevertheless exterior of what seemed like a badly-built cabin. What struck me was their gaze.

A few generations of ladies in Virginia. Photograph from the writer’s family members album. Museum artwork talk “Time and Reflection: Driving Her Gaze.”

What thoughts hid powering their deep penetrating looks? Their bodies recommended a permanence in the Virginia landscape around them. I knew the names of the ancestor moms, but I knew little of their lives. What were their secrets and techniques? What music did they sing? What wishes sat in their hearts? Stirred their hearts? What were the night time sounds and day seems they heard? I preferred to know their ideas about the earth all over them. What frightened them? How did they chat when sitting down with close friends? What did they confess? How did they converse to strangers? What did they conceal? What was girlhood like? Womanhood? These queries led me to creating that explored how they will have to have felt.

Analysis was not sufficient to deliver them to me. Recorded public heritage normally distorted or omitted the tales of these gals, so my background-mapping relied on memories related with emotions. Toni Morrison named memory “the deliberate act of remembering, a variety of willed creation – to dwell on the way it appeared and why it appeared in a unique way.” The act of remembering by poetic language and collage assisted me to far better recognize these ancestor mothers and give them their say.

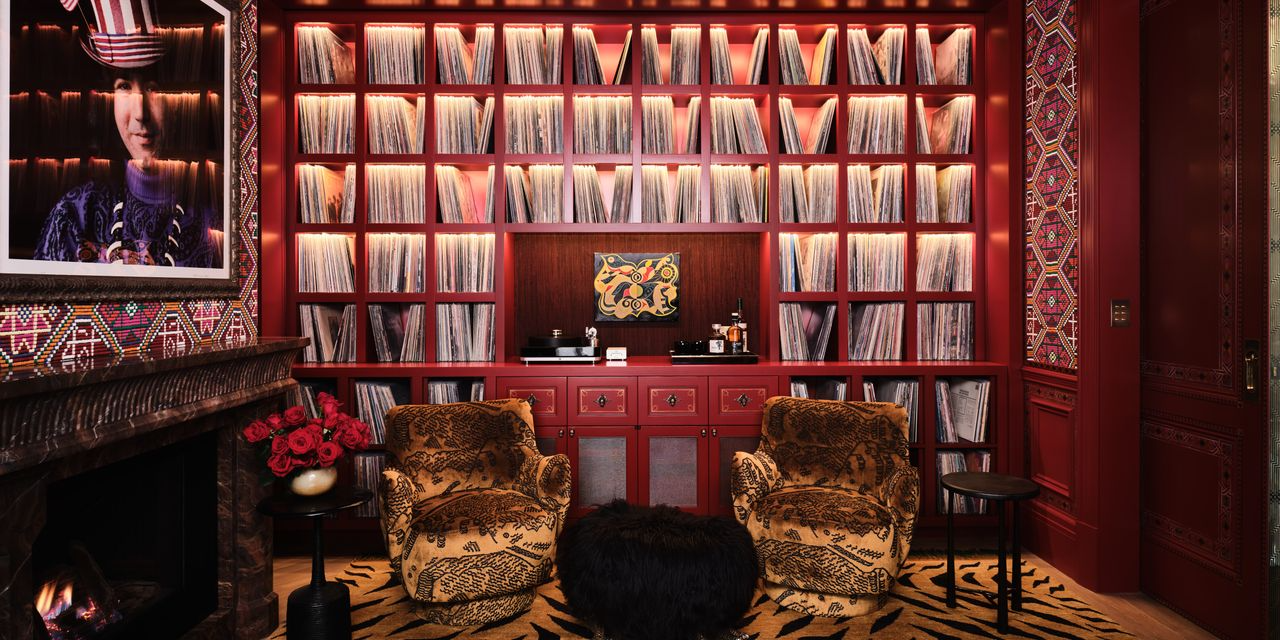

Photos of the artist and visual texts of ancestor mothers hanging in studio at Aminah Robinson home.

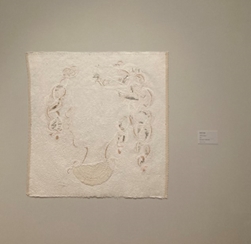

Functioning in Aminah Robinson’s studio, I traveled the line that carries my spouse and children record and my innovative composing crossed new boundaries. The texts I established reimagined “Blood on a Blackberry” in hand-slice designs drawn from traditions of Black women’s stitchwork. As I cut excerpts from my prose and poetry in sheets of mulberry paper, I assembled fragmented reminiscences and reframed unrecorded historical past into visible narratives. Coloration and texture marked childhood innocence, feminine vulnerability, and bits of recollections.

The blackberry in my storytelling turned a metaphor for Black life created from the poetry of my mother’s speech, a southern poetics as she recalled the substances of a recipe. As she reminisced about baking, I recalled weekends accumulating berries in patches alongside region streets, the labor of little ones gathering berries, placing them in buckets, going for walks alongside roads fearful of snakes, listening to what could possibly be in advance or concealed in the bushes and bramble. Those people memories of blackberry cobbler advised the handwork, craftwork, and lovework Black families lean on to survive wrestle and rejoice life.

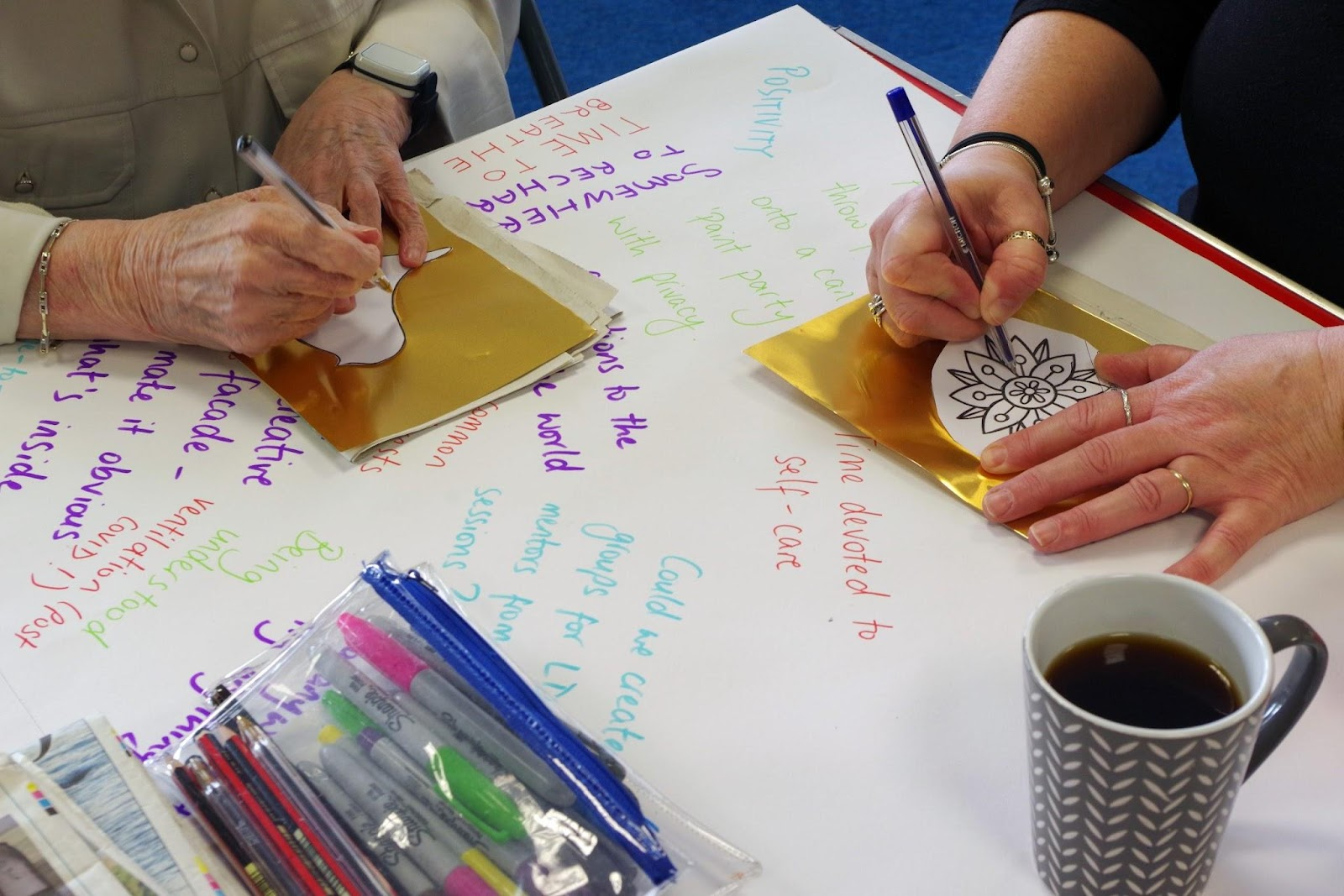

In a museum chat on July 24, 2022, I connected my imaginative encounters throughout the residency and shared how thoughts about ancestors infused my storytelling. The Blood on a Blackberry assortment exhibited at the museum expressed the enlargement of my crafting into multidisciplinary sort. The layers of collage, silhouette, and stitched styles in “Blood on a Blackberry,” “Blackberry Cobbler,” “Braids,” “Can’t See the Street Ahead,” “Sit Side Me,” “Behind Her Gaze,” “Fannie,” “1870 Census,” and “1880 Census” confronted the previous and imagined reminiscences. The remaining panels in the exhibit launched my tribute to Fannie, born in 1840, a probably enslaved foremother. Even though her life time rooted my maternal line in Caroline County, Virginia, study unveiled sparse strains of biography. I faced a lacking website page in historical past.

Photograph of artist’s gallery converse and discussion of “Fannie,” “1870 Census,” and “1880 Census.”

Aminah Robinson comprehended the toil of reconstructing what she referred to as the “missing web pages of American history.” Employing stitchwork, drawing, and portray she re-membered the earlier, preserved marginalized voices, and documented historical past. She marked historic times relating daily life times of the Black group she lived in and loved. Her do the job talked back to the erasures of history. Therefore, the house at 791 Sunbury Street, its contents, and Robinson’s visual storytelling held distinctive indicating as I worked there.

I wrote “Sit Facet Me” in the course of quiet hours of reflection. The days just after the incidents in “Blood on a Blackberry” needed the grandmother and Sweet Boy or girl to sit and collect their strength. The commence of their discussion came to me as poetry and collage. Their story has not ended there is much more to know and assert and picture.

Photograph of artist cutting “Sit Aspect Me” in studio.

Photograph of “Sit Aspect Me” in the museum gallery. Graphic courtesy of Steve Harrison.

Sit Facet Me

By Darlene Taylor

Tasting the purple-black spoon from a bowl mouth,

oven heat sweating sweet nutmeg black,

she halts her kitchen baking.

Sit facet me, she states.

I want to sit in her lap, my chin on her shoulder.

Her heat, darkish eyes cloud. She leans forward

shut adequate that I can follow her gaze.

There’s significantly to do, she claims,

positioning paper and pencil on the table.

Publish this.

Someplace out the window a chicken whistles.

She catches its voice and styles the substantial and very low

into words and phrases to describe the wrongness and lostness

that took me from college. A woman was snatched.

She recall the ruined slip, torn book pages,

and the flattened patch.

The terms in my arms scratch.

The paper is too limited, and I just can’t publish.

The thick bramble and thorns make my hands continue to.

She can take the memory and it belong to her.

Her eyes my eyes, her pores and skin my skin.

She know the ache as it handed from me to her,

she know it like sin staining generations,

repeating, remembering, repeating, remembering.

Remembering like she know what it come to feel like to be a lady,

her fingers slide across the vinyl desk surface to the paper.

Why cease producing? But I really do not respond to.

And she don’t make me. Rather, she qualified prospects me

down her memory of getting a lady.

When she was a female, there was no school,

no publications, no letter composing.

Just thick patches of green and dusty crimson clay road.

We take to the only highway. She appears to be significantly taller

with her hair braided from the sky.

Just take my hand, sweet little one.

Collectively we make this stroll, hold this old street.

A milky sky flattens and eats steam. Clouds spittle and bend very long the street.

Photographs of slice and collage on banners as they hang in the studio at the Aminah Robinson dwelling.

Blood on a Blackberry

By Darlene Taylor

The street bends. In a spot exactly where a lady was snatched, no one says her name. They converse about the

bloody slip, not the misplaced girl. The blacktop road curves there and drops. Just cannot see what is in advance

so, I listen. Bugs scratch their legs and wind their wings earlier mentioned their backs. The street sounds

secure.

Just about every day I walk on your own on the schoolhouse street, trying to keep my eyes on where by I’m going,

not where by I been. Bruises on my shoulder from carrying textbooks and notebooks, pencils and

crayons.

Pebbles crunch. An motor grinds, brakes screech. I stage into a cloud of pink dust and weeds.

The sandy flavor of highway dust dries my tongue. More mature boys, imply boys, cursing beer-drunk boys

laugh and bluster—“Rusty Lady.” They generate quick. Their laughs fade. Feathers of a bent bluebird impale the road. Sunshine beats the crushed bird.

Chopping via the tall, tall grass, I decide up a stick to alert. Music and sticks have ability more than

snakes. Bramble snaps. Wild berries squish underneath my toes. The ripe scent tends to make my tummy

grumble. Briar thorns prick my pores and skin, producing my fingertips bleed. Plucking handfuls, I eat.

Blood on a blackberry ruins the taste.

Textbooks spill. Backwards I slide. Webpages tear. Lessons brown like sugar, cinnamon,

nutmeg. Blackberry stain. Thistles and nettles grate my legs and thighs. Coarse

laughter, not from inside of me. A boy, a laughing boy, a imply boy. Berry black stains my

dress. I operate. Household.

The sunlight burns by kitchen windows, warming, baking. I roll my purple-tipped fingers into

my palms.

Sweet child, grandmother will say. Good lady.

Tomorrow. On the schoolhouse street.

Photographs of artist reducing textual content and discussing multidisciplinary writing.